Blogging Team 11: Rimon Ghebremeskel, Tapi Goredema, Yi Ping, Elijah Smith, Samrawit Yemane

News: Our DNA is at risk of hacking, warns scientists

Slides from Team 3 (Lily Egenrieder, Mandy Le, Lara Mahajan, Kate McCray, Shreeja Tangutur)

Team 3 led a discussion about the growing involvement of AI in medicine, biology, and Genomics. They highlighted the benefits and risks of AI in these fields, one risk being vulnerability to the cybersecurity of Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) methods, which are more computer-based than their Sanger counterpart.

In early 2025, a growing number of scientists and technologists have begun sounding the alarm on a surprising new risk between the realms of biology and computing: the cybersecurity vulnerabilities of genetic data. As DNA sequencing becomes cheaper and faster, massive amounts of human genome data are now stored, shared, and analyzed across networks worldwide.

Researchers have discovered that these biological data streams can be targeted much like traditional digital systems, for example, by embedding malicious code into synthetic DNA or exploiting machine-learning models trained on genomic datasets. These findings raise urgent questions about privacy, ethics, and safety, especially as artificial intelligence becomes more deeply integrated into healthcare and biotechnology.

Relevance to AI/topic of discussion

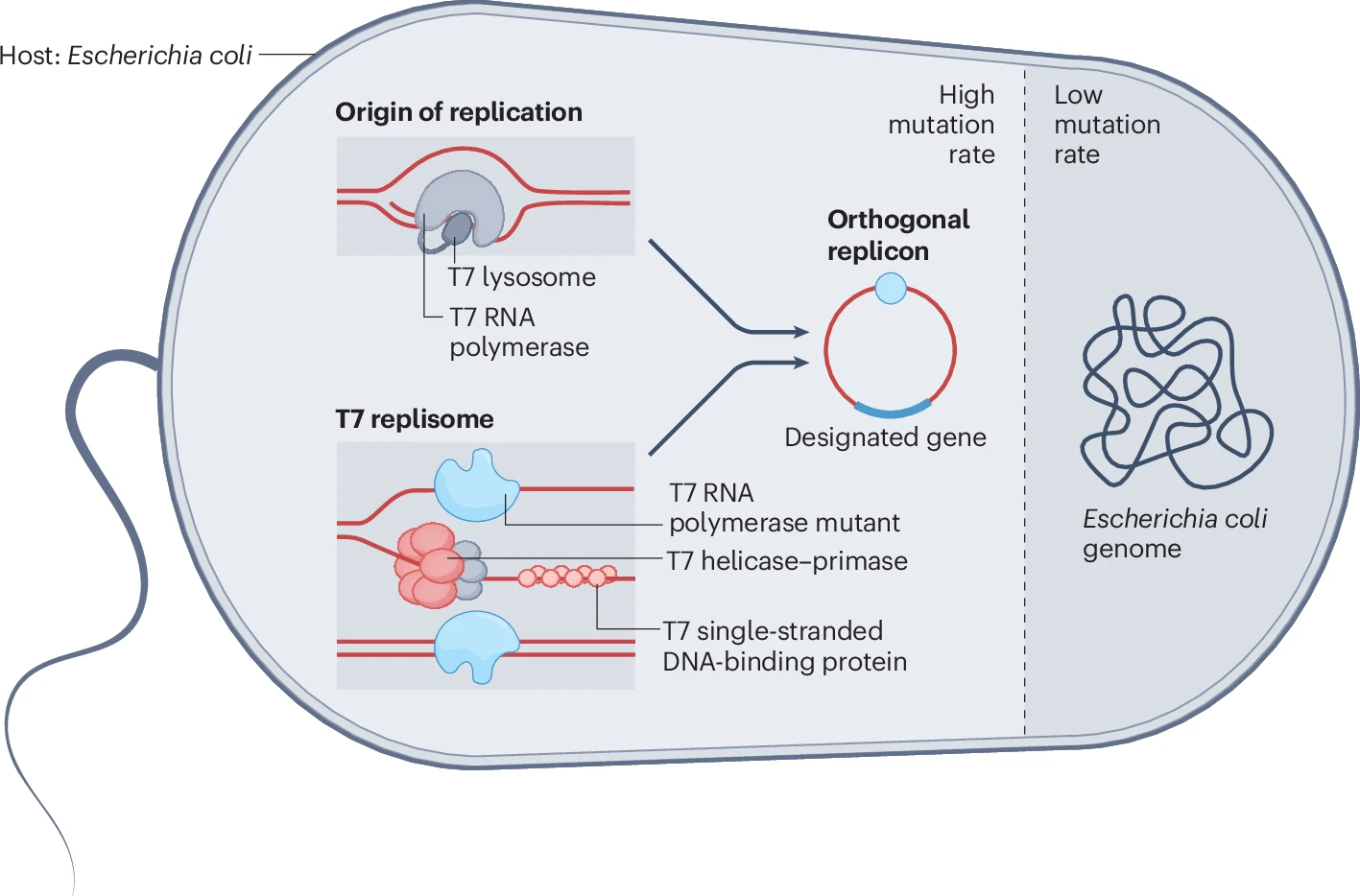

With technology like AlphaFold and T7-Oracle advancing and integrating into fields of medicine and biology, conversations about AI’s impact and implications have increased. Genomics today isn’t just about biology; it has become deeply tied to computers and AI. Tools like AlphaFold, AI-based variant analysis, and platforms like T7-ORACLE are helping scientists interpret DNA, predict protein behaviour, and speed up evolution, demonstrating that AI can solve what used to take us years in a couple of days.

Despite the benefits, studies testing AI in medicine show that models can make different recommendations for identical patients based only on socioeconomic or demographic information. This is problematic as it can lead AI to choose a suboptimal diagnosis for a patient, disregarding medical necessity, and often choosing more advanced diagnostic tests for high-income patients while advising lower-income ones to undergo no further testing.

This is why AI bias and genomics belong in the same conversation. As genetic data becomes more digital and AI-driven, these biased decisions will pose a huge risk to patients, creating unfair outcomes if not unsafe/dangerous ones. If these models continue to be trained on incomplete and biased data, they will only be reinforcing existing inequalities in healthcare instead of fixing them with the new speed and computational power they provide.

Conceptual diagram of the T7-ORACLE accelerated protein evolution system in E. coli. (Source: Nature)

Discussion

The discussion focused on how genomics has become more digital and what risks come with that change. The group explained that modern DNA sequencing methods, especially Next Generation Sequencing (NGS), rely heavily on computers, software, and online data storage. While this makes genetic research faster and more accessible, it also creates cybersecurity risks just like any other setting where untrusted parties may have control over input data. The slides showed that DNA data can be hacked or manipulated, including through synthetic DNA–encoded malware or AI-based attacks on genetic databases. Students also talked about how these risks connect to AI in healthcare.

Lead Discussion: Protein Structure Prediction (AlphaFold)

Team 7 Slides (David Hu, Seth Lifland, Grace Kitthanawong, Pallavi Mamillapalli, Aryan Thodupunuri)

Readings:

-

John Jumper, Richard Evans, Alexander Pritzel, Tim Green, Michael Figurnov, Olaf Ronneberger, Kathryn Tunyasuvunakool, Russ Bates, Augustin Žídek, Anna Potapenko, Alex Bridgland, Clemens Meyer, Simon A. A. Kohl, Andrew J. Ballard, Andrew Cowie, Bernardino Romera-Paredes, Stanislav Nikolov, Rishub Jain, Jonas Adler, Trevor Back, Stig Petersen, David Reiman, Ellen Clancy, Michal Zielinski, Martin Steinegger, Michalina Pacholska, Tamas Berghammer, Sebastian Bodenstein, David Silver, Oriol Vinyals, Andrew W. Senior, Koray Kavukcuoglu, Pushmeet Kohli, and Demis Hassabis. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature, 26 August 2021. [PDF Link]

Optional: There is an “AlphaFold 3” now, described in this paper, but you are not expected to read this one. -

David Ampudia Vicente and George Richardson. AI in Science: Emerging evidence from AlphaFold 2. 25 November 2025. [PDF Link] (Original paper and full report is available for https://www.innovationgrowthlab.org/resources/ai-in-science-alphafold-2, but you are only expected to ready the summary report in the PDF Link.)

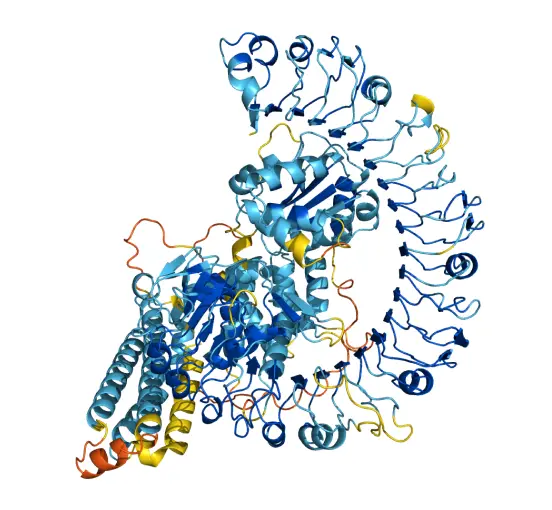

Figure 2: Protein structure produced by AlphaFold. (Source: AlphaFold Protein Structure Database)

The lead discussion for this class was presented by Team 7 regarding AlphaFold and Protein Structure Prediction. Team 7 discussed the potential benefits and concerns of AlphaFold’s involvement in protein research.

AlphaFold’s most impressive feat is its ability to generate remarkably accurate structure predictions of unreleased protein sequences. The paper reports on AlphaFold 2’s success on the CASP14 competition, which is a blind test containing new experimentally solved and undisclosed structures, to which researchers/scientists can submit their predictions and gauge their accuracy. Unlike other computational methods, which can be complicated, expensive, or incorrect, AlphaFold was able to predict novel and large protein sequence structures with near experimental accuracy most of the time and often within the width of an atom, showing that the model can not only memorize, but also learn and extrapolate from given data.

AlphaFold cannot guarantee prefect accuracy, so empirical work is still needed to verify predicted structures when predicting novel protein sequences. Despite this, scientists can use AlphaFold’s prediction in conjunction with other computational methods, such as the evolutionary and physics-based models, to drastically reduce the time it takes to determine a protein’s 3D structure. The article also highlighted AlphaFold’s confidence score, which is usually correct for sections of the structure, providing a strong and realistic model for scientists to map from.

AlphaFold has already had substantial practical impact. In 2021, AlphaFold 2 was able to predict the Vg protein found in honeybees, which can help shorten the breeding cycle from a year to a couple of weeks, slowing down the extinction of honeybees. It also has involvement in sustainability efforts. Scientists were able to replicate the GLYK enzyme found in plants, an important enzyme for photosynthesis, without the same temperature weakness.

AlphaFold’s ability to speed up protein structure research raises broader questions about AI autonomy in medicine and whether AI physicians can replace human ones. AlphaFold’s ability to extrapolate and generalize original solutions shows that AI could be able to autonomously solve critical and novel problems without needing a direct precedent, which is a huge advantage in the medical field.

Discussion

Team 7 mentioned many topics of discussion revolving around the use of AlphaFold and the future of AI in scientific research. Some questions were centered on conversations between table group members, but the larger discussion questions and their respective student responses became more about the broader implications of AlphaFold in conducting, as Team 7 stated, “good science.”

Question 1: Does AI change what it means to “do science”?

Team 7 argues that AI does change what it means by shifting the scope of problems that can be solved. One student responded to this question by stating that AI does not change what it fundamentally means to do science, but rather changes the process in which we do it. As they put it, “the scientific method does not change,” however, the tools that we use to pursue scientific research evolve over time. AI is simply just another tool in the toolbelt.

The discussion team then proposed a follow-up question for the class to ponder: Do we believe that AI will get to the point where it will perform new discoveries on its own, or will it follow human direction? Additionally, Professor Evans pointed out that AI is now being used to generate hypotheses for scientists to use in driving research. How will what it means to be a scientist change when much of the research agenda is driven by AI tools?

Question 2: Does AI narrow what “good science” looks like?

Team 7 opened this discussion with the authors’ findings in the AlphaFold 2 Summary Report. The authors stated that AlphaFold 2 “lowers the cost barrier and reduces the risks associated with research portfolio diversification,” which may help divert research efforts and resources to more unexplored areas of protein science. However, the discussion team also mentioned how there is discourse as to whether AI will either contribute to or help mitigate the “spotlight effect,” which is a phenomenon where research is focused on existing, data-rich problems and structures.

Some students shared their disagreement with the discussion question. One student asserted that since AI programs like AlphaFold 2 are tools for scientists to use, it is more of the scientists’ responsibility to know how to narrow their focus. AlphaFold 2 cannot perform research on its own. A member of Team 7 shared the perspective that even if AI could narrow the scope of pursued questions, it is still good to solve problems in any case, no matter how easy and well-established they may be.

Question 3: If AlphaFold is getting protein structures right most of the time, does it still make sense to run expensive lab experiments to confirm them? And is it okay if we don’t fully understand how the model works, as long as the output is correct?

Team 7 led with the idea that “high predictive accuracy does not necessarily imply mechanistic understanding”. In essence, AlphaFold 2, along with many other AI systems, works as a “black box” where most users only acknowledge that its protein structure predictions are accurate; however, they do not understand how the conclusion was reached. In light of this, should researchers place so much emphasis on the results of AlphaFold 2?

One student’s response was a more nuanced take. The student affirmed that we should not take an AI’s word at face value, especially when conducting experiments. On the other hand, researchers do not necessarily need to know the nitty-gritty of how the model works. If the model proves useful, then it should be recognized as such, but it does not discount the importance of verification through experimentation.

Overall, although the implications of AI systems such as AlphaFold hold a strong potential to reshape how science is conducted in the future, the class seemed to hold the idea that the current process of pursuing science is in no danger of change. Optimistically, AI can divert resources to open entirely new fields of research to advance the scope of our knowledge. Only time will tell where it can push us next.